Urgent Lead Pipe Replacement Projects Now a Funding Priority

By ROB McMANAMY

As the Mississippi state capital entered its second month of an emergency boil order for unsafe drinking water this September, the bitter battle between its governor and the city mayor intensified over federal infrastructure funding that the state had previously turned down. Meanwhile, local residents, schools, businesses, and municipal services all scrambled to adjust their fall planning now to focus on short-term survival in addition to longer-term solutions.

But as stark as the City of Jackson's fate had become, seemingly overnight, it was ultimately not all that different from recent drinking water crises that had previously struck and continue to concern the aging cities of Flint (MI), Milwaukee, Chicago, New York, Boston, and others. In fact, Mississippi's latest Infrastructure Report Card from the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) gave its drinking water systems a grade of 'D' in 2020 and warned then that the state needed to increase related investments drastically:

In 2015, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimated that Mississippi needs $4.8 billion over the next 20 years to fund safe drinking water infrastructure for the people of Mississippi. Much of the state’s current drinking water infrastructure is beyond or nearing the end of its design life, with older systems losing as much as 30-50% of their treated water to leaks and breaks...

According to the Mississippi Department of Health’s (MSDH) Bureau of Public Water Supply, the state has 1,170 public water systems that must comply with the Federal Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). The condition and capacity of Mississippi’s drinking water infrastructure influences the systems’ ability to treat, store, and deliver potable drinking water at adequate pressure to the state’s population. In Mississippi, the percent difference of billable water to treated water (non-revenue water or water losses) averages approximately 15%; older systems lose as much as 50% of the water treated. The high leakage rates and water main breaks are mostly due to the aging pipes of legacy water systems in the state. Some pipes were laid as early as the 1920s, while other water systems consist of pipes that were laid from the 1940s to 1980s. Many of these networks have aged past their useful life span.

On Sept. 7, national ASCE President Dennis Truax, himself a Mississippi resident, said, "My heart goes out to all of those impacted in Jackson. No one should be without safe drinking water in the 21st Century."

He added, "All of the utilities in Mississippi are doing what they can to protect the citizens they serve. However, with very limited resources, these systems have become increasingly susceptible to water main breaks, treatment facility problems, and other infrastructure failures. Funding from the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) is providing significant resources to the state’s drinking water systems -- $429 million over five years."

"While this figure is not enough to completely reverse the decline of the state’s systems, improved planning, data, and financial assistance is a crucial step to help utilities tackle deferred maintenance projects, and better withstand extreme precipitation, wind, and other natural hazards," said Truax.

Nationally, of course, ASCE has been sounding the alarm for decades, ever since launching its overall U.S. Infrastructure Report Card in 1998 and re-issuing grades every four years in 16 categories, ranging from transportation and energy to water systems and waste management. Ironically, the most recent report card in 2021 actually raised the national grade for drinking water systems from 'D' to 'C-.' But that assessment was made well before the latest disastrous failures in Jackson.

Even so, the 2021 ASCE Infrastructure Report Card pulled no punches in reiterating its dire warnings for the U.S. drinking water sector:

Our nation’s drinking water systems face staggering public investment needs over the next several decades. ASCE’s 2020 economic study, “The Economic Benefits of Investing in Water Infrastructure: How a Failure to Act Would Affect the U.S. Economic Recovery” found that the annual drinking water and wastewater investment gap will grow to $434 billion by 2029. Additionally, the cost to comply with the EPA’s 2019 Lead and Copper Rule is estimated at between $130 million and $286 million. Drinking water utilities also face increasing workforce challenges. Much of the current drinking water workforce is expected to retire in the coming decade, taking their institutional knowledge along with them. Between 2016 and 2026, an estimated 10.6% of water sector workers will retire or transfer each year, with some utilities expecting as much as half of their staff to retire in the next five to 10 years.

That said, the positive turn taken last November in the enactment of the new Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (IIJA) finally promises actual progress. As a result, the federal government is providing some $55 billion to support capitalization projects through the Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (SRF) programs, including $15 billion specifically for lead service line replacement projects. EPA estimates there are 6 to 10 million lead service lines still in the ground across the country

In May, EPA announced that it is making available $7.28 billion in new federal grant funding for the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF). This funding can be used for loans that help drinking water systems install treatment for contaminants, improve distribution systems by removing those lead service lines and improve system resiliency to natural disasters such as floods.

"I have visited with and heard from communities in Chicago, Flint, Jackson, and many other areas that are impacted by lead in drinking water,” said EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan last December. “These conversations have underscored the need to proactively remove lead service lines, especially in low-income communities. The science on lead is settled—there is no safe level of exposure and it is time to remove this risk to support thriving people and vibrant communities.”

At that time, the Biden Administration announced a new "whole of government Lead Pipe and Paint Action Plan," which followed an EPA review of the latest revisions to the original Lead and Copper Rule, which had first gone into effect in 1991. Announced in December, the new Lead and Copper Rule Revisions (LCCR) were subsequently delayed twice, but went into effect in June. Their goal is "to advance critical lead service line inventories that are necessary to achieve 100% removal of lead service lines."

EPA said it would also develop a new proposed rule, the Lead and Copper Rule Improvements, to help to implement and complete the replacement projects "as quickly as is feasible." EPA also intends to consider opportunities to strengthen tap sampling requirements and explore options to reduce the complexity and confusion associated with the action level and trigger level, with a focus on reducing health risks in more communities.

At a June visit to the Pittsburgh offices of the AFL-CIO, EPA Administrator Regan joined Vice President Kamala Harris in announcing the LCR improvements and to cite tangible evidence of progress already this year. Toward that end, the White House noted that:

- The City of Pittsburgh, PA, has budgeted $17.5 million to partner with the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority to complete projects to remediate lead in drinking water;

- The City of Toledo, OH, plans to replace all private lead service lines in the city (approximately 3,000 lines) at no cost to homeowners. Additionally, the City will replace many public lead service lines co-located with private lines;

- The City of Buffalo, NY, has budgeted $10 million for an expansion of its ROLL program so that at least an additional 1,000 homes can have their lead water service lines replaced. The City has already successfully replaced the lines in 500 homes and this expanded capacity will more than double its impact;

- The Village of Elberta, MI, has received $3.4 million in grant and low-interest loans from USDA, leveraging an additional $2 million in state assistance, to improve their water system and remediate lead. Approximately, 79 percent of the service laterals in the water distribution system are known or suspected to contain lead. USDA has an additional $23.8 million in projects containing lead remediation that are nearing approval and other applications in development;

- The City of Linwood, KS, has been awarded $350,000 award by the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture (USDA) for its Water System Improvements Project. Leveraging $499,586 in HUD’s Community Development and Block Grant funds and $150,000 in applicant contribution, this project will enable Linwood to replace approximately 75 cast iron service lines that may contain lead joints and to make other necessary improvements to the distribution system;

- The Anson Madison Water District in Maine has received a $6-million low-interest loan and $3.5-million grant to mitigate lead exposure for 3,700 residents. The work will replace lead lines and remediate lead plumbing, pipes, and paint in two area high schools and local child care facilities;

- Columbus County, NC, has been awarded a $9.5 million rural development grant from USDA to cover the construction and cost overrun of a new replacement school facility housing Pre-K through 8th grade. This new facility replaces two school facilities ranging from 60-94 years old with asbestos in almost all flooring and lead paint throughout.

Appearing with U.S. Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Secretary Marcia Fudge, Vice President Harris and Administrator Regan also announced an additional $500 million for states and local governments to reduce lead exposure and build healthier homes via the new Justice40 Initiative. That program allows states and municipalities to apply for the funds, targeting disadvantaged businesses and communities.

Even as the federal government now moves forward more aggressively some environmental advocates are concerned the size of the investment may not be enough and the initial targets may not be the most needed.

"While there is much to like about this landmark federal investment in replacing lead service lines, key improvements are needed to equitably distribute funding and align this assistance with need," said Cyndi Roper, a senior policy advocate in Michigan for the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC). "This is because the current state-by-state funding distribution formula is based on past drinking water infrastructure needs assessments that did not include the cost of fully replacing lead service lines."

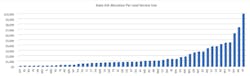

Writing in July on the NRDC blog, Roper explained, "Every state has lead service lines, but some have significantly more than others. The highest concentration of lead service lines delivering water to homes are in the upper Midwest and Northeast states, as well as Texas... The states with the most lead service lines—like Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio—will receive far less per lead line than states with fewer lead service lines. For example, the states of Michigan and Missouri will receive an estimated $151 per lead service line, while some states with fewer lines will receive an estimated $7,441 and $10,098 per line, respectively."

Below, NRDC projects the allocation for each of the 50 states.The full data set can be found here.

NRDC says the fix for this problem is for EPA to quickly complete its Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment (DWINSA) and to re-distribute the $15 billion for lead service lines based only on the number of lead service lines in each state or territory.

Of course, if and when those funding allocation revisions happen remains to be seen. But for now, as illustrated by the list above, the number of lead replacement projects moving forward is only accelerating. And the hope, both nationally and locally, is that this long-delayed work will now move quickly enough to avoid the next Flint or Jackson.

##########