Refrigerant Transition: Urgent Advice for Meeting New Deadlines

Engineers dealing with commercial refrigeration or HVAC design will all tell you that, like it or not, the U.S. has started down the path towards reducing the global warming impact caused by refrigerants.

This is due in large part to the new American Innovation and Manufacturing Act (AIM Act), passed by Congress in December of 2020 with bipartisan support, which essentially required the EPA on January 1, 2022, to initiate a high-GWP refrigerant phasedown schedule.

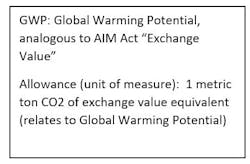

The purpose of the phasedown schedule is to reduce the availability of high Global Warming Potential (GWP) refrigerants and is designed to accelerate the reductions of Carbon Dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions at a national level.

Although states like California have already begun to aggressively reduce their refrigerant based global warming impact, the AIM Act will accelerate the refrigerant transition from the federal level.

Adapted from our October webinar for HPAC Engineering, this article will help the reader to understand what the AIM Act is and how it will affect commercial refrigeration and HVAC designs, along with what end users of refrigerants should be doing now to avoid increases in first costs and operational expenses.

Why now? Why focus on refrigerants?

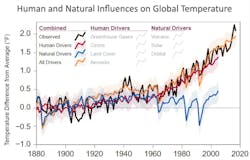

In order to predict how something will affect the bigger picture outlook for your operation, one must first understand why circumstances are changing. Fundamentally, the EPA has determined that higher GWP synthetic refrigerants, like those commonly used in HVAC and commercial refrigeration applications today, are – pound for pound – one of the most significant causes of global warming on the planet.

To put it in perspective, avoiding releases of high-GWP hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) by using low-GWP refrigerants may avoid as much as 0.5°C warming by the end of the century.

GWP impacts on global warming are typically calculated over a 100-year time period. Additionally, HFC refrigerants are considered to be short-lived climate pollutants (SLCP) that are powerful climate forcers with relatively short atmospheric lifetimes. Therefore, reducing the emissions of these short-lived refrigerants will have an immediate impact on reducing the potential for climate changes.

The AIM Act – 3 Parts to Implementation and Refrigerant Phase Down

The AIM Act, or American Innovation and Manufacturing Act, was enacted by Congress in December 2020. The AIM Act provides authority in the form of a Federal Law to be enforced and provided for through the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to address HFC emissions. The AIM Act has three main parts to the rule:

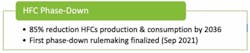

1. Phasing down production and consumption – “Final Rule”;

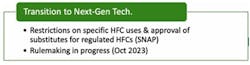

2. Facilitating the transition to next-generation technologies through sector-based restrictions;

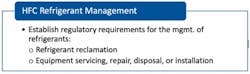

3. Maximizing reclamation and minimizing releases of HFCs from equipment.

AIM 1: Phasedown of HFC Use According to GWP

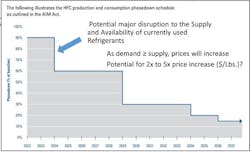

The phasedown of higher GWP HFC refrigerants is the major focus of the first part of the AIM Act. The phasedown is designed to purposely increase the cost for higher GWP refrigerants by lowering their availability in the U.S. market.

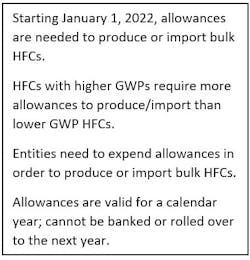

To lower the availability, the EPA set a phase down schedule for all refrigerant based emissions and individual “allocations of GWP or CO2 equivalent emissions” that refrigerant manufacturers must stay under. In other words, refrigerant OEMs will be limited in how much refrigerant they can provide into the marketplace based on the GWP equivalent of their portfolio of refrigerants that they sell.

HFC phasedown is designed to leverage the “natural order of supply and demand” economics, which in a classic sense, if the demand stays the same, limiting the supply of a commodity will naturally cause the price to increase. Refrigerant OEMs will be limited in how much refrigerant they can supply into the market by their individual CO2e allocations, based on historical production or import. This will, in fact, reduce the amount of refrigerant that OEMs can provide into the U.S. market, according to the refrigerant GWP value.

Lowering the availability of higher GWP refrigerants based on “allocations” simply increases pricing pressures.

Supply will be constrained vs. the demand, and therefore, the prices must increase, unless demand for those higher GWP refrigerants reduces accordingly with the amounts allocated to each OEM, according to the phasedown schedule, or the difference in supply is made up from reclaimed refrigerant.

The bottom line is this: higher GWP refrigerants will be more expensive and may have limited availability in certain locations.

HFC production and consumption allowances decreased by 10% in 2022 and by 2036 allowances will be decreased by 85% from historical baselines. It is worth noting that the phasedown allowances are issued by the EPA on October 1st each year, for the following year for planning purposes.

AIM 2 & 3: Facilitating Transition to Next-Gen Tech via Sector-Based Restrictions, Maximizing Reclamation, Minimizing HFC Release

As mentioned earlier, the initial phasedown schedule is the first salvo from the AIM Act. There are two additional portions of the rulemaking that are still in progress; “Facilitating the transition to next-generation technologies through sector-based restrictions” and “Maximizing reclamation and minimizing releases of HFCs”.

Congress set aggressive timelines in the language of the law to implement the refrigerant phased down and allocations. The final two phases have yet to be fully defined, but we can expect them to contain more restrictions on use of refrigerants in different applications and “sectors”, and establish more requirements on reclamation, and equipment servicing, repair, disposal, and installation.

The law gives the EPA authority to regulate HFC refrigerants through sector-based rulemaking and several Technology Transitions have been submitted for review related to stationary air conditioning, chillers, commercial refrigeration, and other end uses. Law further directs the EPA to establish regulations for purposes of maximizing reclamation of refrigerant and minimizing the release of refrigerant from equipment.

One should also expect additional EPA requirements to include HFC record-keeping and reporting, along with the enforcement actions to be potentially taken for any violations. The EPA also seems to be gearing up toward increasing the use of reclaimed refrigerants in certain applications.

What You Should Be Doing Now

I have been in the commercial refrigeration industry for over 25 years and this refrigerant transition is by far the largest market sector disrupter that we will experience.

With uncertainty comes challenge and potentially opportunity, so my advice is to be prepared and act now. Do not wait until you can’t find or afford the refrigerant you use or hear from the EPA that an Enforcement Action is being filed against you.

Below is a short of list of what I would consider the most important steps to be taking now.

1. Know your refrigerant asset inventory.

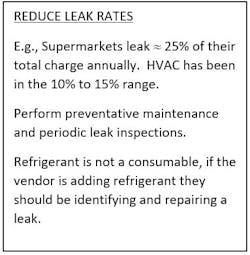

What do you have (in Lbs.) and where do you have it (by equipment type, application, location)? Bring in house or hire an experienced consultant if you are relying on a 3rd party service partner to be responsible for maintaining your asset and servicing documentation. Remember, the Owner has ultimate responsibility for compliance and would most likely be the sole defendant on any Enforcement Actions taken.

2. Set up a method to maintain the refrigerant compliance records.

I would suggest using a Software built and designed for that purpose (single source for all records – consider options other than servicing contractor). I should note that “record keeping” has historically been an easy area to fine companies for non-compliance.

3. Develop a refrigerant management compliance plan.

4. Ensure your technicians and 3rd party servicers are up to speed. They all need to be aware of the Section 608 requirements, and any additional state and local jurisdictional requirements.

5. Determine what you want to do with recovered refrigerants. This includes refrigerants removed during remodel, end of life, or refrigerant change out/retrofit.

6. For new equipment, ask questions of your design engineer and equipment OEM. Make sure you are getting the best long-term solution for your operation.

7. Know where and when natural refrigerants make sense in their applications.

##########

About the authors

Glenn Barrett serves multiple roles as Technical Engineering Lead/Director of Refrigerant Management Solutions and as a Sr. Associate Partner at DC Engineering. He is a veteran in commercial refrigeration design, construction, commissioning, and compliance related issues and is involved in energy modeling, measurement and verification, and is a consultant and speaker on natural refrigerant system design, deployment and best practices. Contact him at [email protected].

Leia Waln is the Refrigerant Compliance Program Manager at Refrigerant Management Solutions, a subsidiary of DC Engineering. Leia has over 10 years of experience working with retail end-users to manage their refrigerant usage and refrigerant compliance tracking and reporting. Leia is considered a Retail Industry Refrigerant Compliance and Reporting subject matter expert, is a leading consultant to the North American Sustainable Refrigeration Council (NASRC), and provides consulting to some of the largest supermarket chains operating in the U.S.

About the Author

Leia Waln

Refrigerant Compliance Program Manager - Refrigerant Management Solutions

Leia Waln is the Refrigerant Compliance Program Manager at Refrigerant Management Solutions, a subsidiary of DC Engineering. Leia has over 10 years of experience working with retail end-users to manage their refrigerant usage and refrigerant compliance tracking and reporting. Leia is considered a Retail Industry Refrigerant Compliance and Reporting subject matter expert, is a leading consultant to the North American Sustainable Refrigeration Council (NASRC), and provides consulting to some of the largest supermarket chains operating in the U.S.

Glenn Barrett

Technical Engineering Lead/Director - Refrigerant Management Solutions and Sr. Associate Partner - DC Engineering

Glenn Barrett serves multiple roles as Technical Engineering Lead/Director of Refrigerant Management Solutions and as a Sr. Associate Partner at DC Engineering. He is a veteran in commercial refrigeration design, construction, commissioning, and compliance related issues and is involved in energy modeling, measurement and verification, and is a consultant and speaker on natural refrigerant system design, deployment and best practices. Contact him at [email protected].