Energy-Saving Opportunities in Green Buildings

The U.S. Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Green Building Rating System provides many paths to certification, some of which result in a more energy-efficient building than others. Thus, just because a building is LEED-certified does not mean significant opportunities for energy savings cannot be found. As the case studies at the end of this article show, savings usually can be had for little or no capital investment by fine-tuning the operations of a building.

ENERGY PERFORMANCE OF LEED-CERTIFIED BUILDINGS

In perhaps the most comprehensive study of the measured energy performance of LEED-certified buildings to date,1 the New Buildings Institute (NBI) found that average energy use in LEED for New Construction and Major Renovations- (LEED-NC-) certified buildings is 25- to 30-percent better than the national average. However, the buildings studied displayed a large degree of scatter, with one-quarter having Energy Star ratings below 50, “meaning they used more energy than average for comparable existing-building stock.”

“How can this be?” you may ask. Are there not energy prerequisites that must be met for LEED certification to be achieved? The answer is, “Yes, but ….”

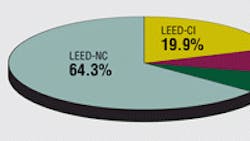

Of the nine LEED rating systems — LEED-NC, LEED for Existing Buildings: Operations & Maintenance (LEED-EB), LEED for Commercial Interiors (LEED-CI), LEED for Core & Shell (LEED-CS), LEED for Schools, LEED for Retail, LEED for Healthcare, LEED for Homes, and LEED for Neighborhood Development — LEED-EB is the only one requiring an actual demonstration of whole-building energy performance, and it accounts for only 8.9 percent of LEED-certified buildings (Figure 1).

Because, of course, the buildings do not yet exist, LEED-NC relies entirely on simulation-model results. According to the NBI study: “Energy modeling turns out to be a good predictor of average building energy performance for the sample. However, there is wide scatter among the individual results that make up the average savings. Some buildings do much better than anticipated; on the other hand, nearly an equal number are doing worse — sometimes much worse” (Figure 2). When individual-building models that inherently have a high degree of variability are used to predict energy use, and LEED points are awarded based on those models, it is not surprising that buildings in which actual energy performance falls short of expectations “slip through the cracks” and become certified.

Only about half of the LEED-NC buildings in the NBI study demonstrated actual energy performance that would qualify for recertification under LEED-EB.

CASE STUDIES

It stands to reason that in a building in which modeled energy performance is much higher than actual energy performance, there will be ample opportunity to reduce energy use. But what about buildings that already are performing well? Are there still savings opportunities to be found? Following are two examples of buildings far exceeding the minimum energy-performance requirement for LEED certification in which significant energy-saving opportunities were found through simple, low-cost energy audits. The common characteristic is an owner motivated to continue to reduce costs and improve energy performance.

Page 2 of 2

One Pacific Square

A 14-story, 240,338-sq-ft Class A office tower in downtown Portland, Ore., One Pacific Square was acquired by Ashforth Pacific Inc. in August 2006. In 2007, the building received its first Energy Star certification. In 2008, it placed second in BOMA (Building Owners and Managers Association) Portland's Office Energy Showdown.

But Ashforth Pacific did not stop there. Through a one-week energy assessment, the company gained new insight into how the building actually was performing, uncovering an additional $27,700 in annual energy savings.

Because Ashforth Pacific had invested in modern control systems and energy-efficient mechanical systems, the savings came through low- and no-cost measures, such as:

- Adjusting the temperature setback to remove an unnecessary system override.

- Lowering the heating set point by 2°F, from 72°F to 70°F.

- Cutting back the lighting schedule by 1 hr to better match tenant schedules and shutting off lights in a particular area of the building at night.

- Installation of a demand-controlled ventilation system to more closely match the amount of outside air to building occupancy.

Westmoor Technology Park

Managed by CB Richard Ellis, Westmoor Technology Park in Westminster, Colo., consists of 10 buildings, nine of which meet LEED-EB requirements for minimum energy-efficiency performance. The Energy and Sustainability team within CB Richard Ellis' Technical Services group selected one of the buildings for an American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers Level I energy audit consisting of a building walkthrough and the deployment of an energy-assessment system.

More than $40,000 in annual savings were identified through the following energy-conservation measures:

- Adjust lighting schedule to better match occupancy.

- Reduce heating set point and raise cooling set point by 2°F.

- Reduce overventilation.

- Add variable-frequency drives to air handlers.

- Take advantage of daylighting to eliminate lighting in lobby atrium.

- Adjust HVAC schedule to remove Sunday operation.

Over the first six months of 2009, energy expenditures were more than $7,000 less than they were over the same period in 2008. Even more savings were expected during the warmer summer months.

CONCLUSION

Opportunities to save energy can be found in all buildings, even those that are performing well. The necessary ingredients are:

- A motivated owner.

- An operations staff incentivized to save energy.

- Tools that increase the visibility of energy performance and potential savings.

While significant investments in energy efficiency are justified for some buildings, most “green” buildings already have systems and equipment capable of delivering high energy performance. It is more a matter of making the buildings run better.

Start by benchmarking the energy performance of a building. Conduct a simple energy audit to identify opportunities to save. Most importantly, follow through on corrective actions — particularly simple changes to building operations that will result in immediate savings.

REFERENCE

-

Turner, C., & Frankel, M. (2008). Energy performance of leed for new construction buildings. Vancouver, WA: New Buildings Institute. Available at http://www.newbuildings.org/downloads/Energy_Performance_of_LEED-NC_Buildings-Final_3-4-08b.pdf

For past HPAC Engineering feature articles, visit www.hpac.com.

The vice president of market development for AirAdvice Inc., a provider of technologies for monitoring and assessing building energy performance, Tim Kensok has 20 years of experience related to HVAC markets, applications, and systems; indoor-air quality; building science; indoor environmental controls; and product development.

LEED-NC Is From Mars, LEED-EB Is From Venus

In 2009, the Energy & Atmosphere (EA) categories of the U.S. Green Building Council's (USGBC's) Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) for New Construction and Major Renovations (LEED-NC) and LEED for Existing Buildings: Operations & Maintenance (LEED-EB) green-building rating systems became much more closely aligned. Both systems require a minimum level of energy (LEED-NC) or energy-efficiency (LEED-EB) performance (Prerequisite 2), and both offer additional points for optimizing energy or energy-efficiency performance (Credit 1).

However, the issue of modeled vs. actual energy performance, which can vary by as much as ±50 percent, is difficult to overcome, with the possibility of buildings becoming LEED-NC-certified on the basis of models that predict a much higher level of performance relative to ANSI/ASHRAE/IESNA Standard 90.1-2007, Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings, than actually is delivered. One possible solution is to require a year of actual energy-consumption data.