Improving Efficiency With Variable-Primary Flow

In 2007, a partnership was formed by the city of Lansing, Mich.; the state of Michigan; Accident Fund Insurance Co. of America and its parent company, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan; developer and construction manager The Christman Co.; Lansing Economic Development Corp.; and Lansing Board of Water & Light (LBWL) to renovate the decommissioned Ottawa Street Power Station in Lansing into Accident Fund's new world headquarters. The partnership required LBWL to construct a separate plant to provide chilled water, which previously was supplied by equipment in the Ottawa Street Power Station's basement.

LBWL contracted with Stanley Consultants to provide engineering and construction services for the new Roy E. Peffley Chilled Water Plant. The consulting firm used four new 2,000-ton electric centrifugal chillers in the Peffley plant, which replaced the Ottawa Street Power Station's four 2,000-ton steam-turbine centrifugal chillers. Additionally, one of the Ottawa facility's 2,000-ton electric units was relocated to the new plant.

Several goals were established for the new plant's construction:

- Improved energy and operational efficiency. To save energy, several environmentally friendly, yet economical, choices were made by the plant's project team.

- Complementary architecture. The new plant is visible in downtown Lansing, so the exterior design was of critical importance.

- Budget control and building information modeling (BIM). It was important to maintain costs throughout the project and keep change orders to a minimum with the use of BIM.

- Improved maintenance operations. Because maintenance access to equipment at the Ottawa Street Power Station was extremely tight, LBWL sought to improve maintenance operations at the new plant.

Chiller Selection

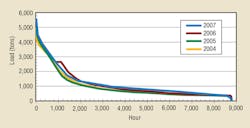

First, the number and size of the chillers for the Peffley plant had to be determined. To aid the chiller-selection process prior to design, the project team evaluated recent historical data for the production and utilization of chilled water.

A historical review of chilled-water loads for the buildings to be served was completed, and a load-duration curve was created (Figure 1). The curve indicated the chilled-water system had a peak load just short of 5,000 tons. Although loads of 1,000 tons or less occurred during most operational hours, LBWL expected loads to increase when new buildings were added to the loop. As a result, 2,000-ton chillers were utilized and part-load performance was maximized for the initial years of operation. Three chillers were installed to meet peak load, and a fourth unit provided “N+1” redundancy. Although the 2,000-ton electric motor-driven chiller was relocated to the new plant, it was not placed into operation. It will be connected and placed into service after load growth has occurred.

Energy/Operational Efficiency

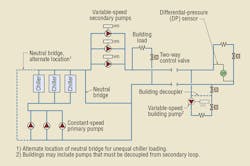

Chilled-water pumping. The Ottawa Street Power Station's chilled-water plant utilized a primary-secondary pumping scheme to deliver chilled water. A primary-secondary system consists of two circuits: a constant-volume production loop (primary) and a variable-volume distribution loop (secondary). The primary loop circulates chilled water through chillers, and the secondary loop circulates chilled water through a distribution system (Figure 2).1

In the past, chiller manufacturers required a constant chilled-water flow rate through evaporator tubes, necessitating a constant-flow loop. A secondary loop operated with variable flow by utilizing variable-speed drives on pump motors. This allowed a system to vary flow rate with cooling load via the positioning of two-way control valves. A neutral bridge or decoupler was used to hydraulically separate the primary and secondary loops. The hydraulic independence of each loop prevented variable flow in the secondary loop from influencing constant flow in the primary loop.2

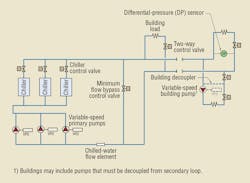

With advances in chiller-control technology, chiller manufacturers now can allow flow variation through an evaporator. As a result, the neutral bridge can be eliminated, and a single set of pumps (with variable-speed drives) can be used to deliver chilled water. Known as a variable primary-flow system, this allows flow to be varied according to cooling load.

The constant-flow primary pumps within a primary-secondary system represent a large energy user that remains constant as long as the pumps are in operation. No reduction in this type of pump energy is possible with a decreasing cooling load. A variable-primary-flow system has a single set of pumps that use only enough electrical energy needed for the corresponding load. However, there is a limitation to the savings. Chiller manufacturers typically limit the range of evaporator-tube velocities from 5 to 10 fps (although some chiller manufacturers allow a wider range), thereby limiting how much flow and pump energy can be reduced. To protect chillers, a bypass is used to prevent chilled-water flow from dropping below a set limit (Figure 3).

By converting from a primary-secondary to variable-primary-flow system, the project team estimated pump energy was reduced by 10 to 20 percent. Variable-primary-flow systems also can save energy by mitigating the effects of low-delta-T syndrome.

Low-delta-T syndrome. Chilled-water-plant performance is not simply the sum of a plant's rated capacity; it must include the performance of the chilled-water-distribution system. Inefficient use of chilled water results in a lower return-water temperature, which, in turn, decreases chiller temperature differential (delta-T).3

Because a chiller's usable capacity is directly proportional to evaporator flow rate and temperature differential, it follows that as delta-T decreases, so does a chiller's capacity, unless there is a corresponding increase in chilled-water flow rate.

The causes of low-delta-T syndrome primarily are related to building operation and, in many cases, cannot be controlled by chilled-water-plant operators. However, a chilled-water plant can combat lower-than-desired delta-T using a variable-primary-flow system to allow variable flow through a chiller evaporator.

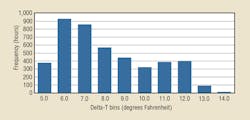

The Peffley plant's variable primary flow. The Peffley plant's project team reviewed hourly historical data from fiscal year 2007 (the most recent data at the time) to determine the range of chilled-water delta-T. To complete the analysis, histograms and data plots were developed. The histograms allowed the team to determine how much the delta-T varied during the year and what delta-T the system experienced during the majority of its operating hours.

The initial analysis revealed that the average annual delta-T for 2007 was 6.8°F, but the temperature had been lowered by the number of hours the system had operated on free cooling. When these hours were disregarded, the average delta-T improved to 7.6°F. Figure 4 shows the distribution of chilled-water temperature differential during the “chiller season.” For just over 60 percent of the chiller season, the delta-T was 8.0°F or lower; this jumped to almost 80 percent for temperatures lower than 11.0°F. Because the Ottawa Street Power Station's chillers originally were designed for 14°F, there still was a significant amount of time during which the system experienced low-delta-T syndrome.

LBWL's long-term goal is to operate the chilled-water system at a high delta-T. Although this is not likely to occur for a while, the variable primary-flow system can help the plant handle periods of low delta-T in the interim.

Design temperature differential and operating range. Because of the range of operating delta-Ts, the project team's next challenge was to determine the plant's design temperature differential. To make this determination, the team investigated the performance, flow range, and costs of several 2,000-ton chillers optimized at delta-Ts within the range described in Figure 4. First, chiller performance was evaluated for a range of chilled-water temperature differentials. Selections were solicited from multiple manufacturers, and it was determined that chiller performance (non-standard part-load value) was comparable at differing delta-Ts with only a 2-percent difference over the range considered. Because energy performance was not a deciding factor in selecting design delta-T, other factors were considered to evaluate performance at off-design conditions.

With delta-Ts of 5°F to 14°F, the flow rate of the 2,000-ton chillers varied from 9,600 to 3,430 gpm. Upon further consideration, the delta-T range was changed to 7°F to 16°F (6,800 to 3,000 gpm) to stay below the maximum flow rate allowed by chiller manufacturers and allow the desired 16°F delta-T to develop over time.

Finally, the chillers' capital costs were considered; they did not vary significantly until a delta-T of 8°F was reached. The cost of the chiller then increased, resulting in a premium for design optimization up to this point.

Based on these factors, the project team selected a design delta-T of 10°F, with an operating range between 7°F and 16°F. The Peffley plant is capable of handling lower delta-Ts without limiting its ability to operate at a higher delta-T in the future. With the implementation of a variable primary-flow system and the selected operational delta-T range, the project team estimated a chiller energy savings of 2 to 4 percent.

Free cooling. Another energy-saving measure included the use of a 2,000-ton free-cooling heat exchanger. It allows chillers to be shut down when it is cool outside and the building cooling load is low. The system transfers heat directly from chilled water to condenser water, offsetting the need for operating chillers. Relocated from Ottawa, the heat exchanger utilizes the same chilled-water distribution pumps and condenser water pumps that the chillers employ. Therefore, the additional cooling system required a minimal capital investment for piping, valves, and controls.

LBWL uses the free-cooling system instead of a centrifugal chiller from December through February. The free-cooling system allows LBWL to meet most of the daily chilled-water demand in periodic service runs during late fall and early spring, weather permitting. At a design temperature of 44°F, the system is capable of producing an amount of chilled water equivalent to that produced by an electric centrifugal chiller. The free-cooling system's number of operational hours offsets the need for electrically generated chilled water, saving energy and reducing the building's carbon footprint.

Architectural Considerations

The Peffley plant is located near the heart of downtown Lansing on the Capitol Loop highway, near the state capitol building and several state office buildings. A primary project objective was to integrate the plant into the surrounding architecture.

Because of site space considerations, eight cooling-tower cells were located on the plant's roof. To conceal them, the project team used architectural louver screens, but the screens made the building mass too large. Horizontal and vertical exterior-insulation-finishing-system accents were added to break up the mass. The vertical accents provided an opportunity to include colored light-emitting diodes to accentuate these features during night hours. A combination of decorative masonry block, brick, and glass was used to construct the building.

Budget Control and BIM

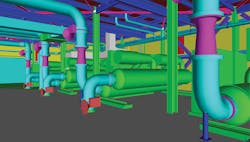

The project operated under a very tight budget. To help minimize the possibility of change orders during construction, the project was designed utilizing BIM. This design approach integrates current technology with the design process to improve communication, identify potential problems early, and provide engineers and designers with vital resources.

BIM software modeled the plant in 3D with an interference manager to identify potential conflicts early in the design process. The software produced structural models with analytical features; architectural models for uses such as space planning; mechanical models of equipment, piping, and HVAC systems; electrical models of equipment and cable tray; and a database linked to piping and instrumentation diagrams with information on valves and instruments. The models then were used to produce traditional construction drawings, specifications, and data sheets. The resulting BIM model provided LBWL personnel and the project construction manager with valuable information on the project design and assisted in resolving clarifications.

Change orders totaled less than 2.4 percent of the project contract value, and the project was completed within its $20 million budget.

Maintenance Operations

Despite limited site space, another project objective was to improve accessibility for equipment maintenance. To this end, equipment was arranged to preserve an open-access aisle on the operating floor, which allows equipment removal without interruption of plant operations. Additionally, the operating floor was designed so chillers and heavy electrical equipment could be moved without the need for floor shoring.

To further facilitate maintenance, monorails were provided over each chiller driveline and for each row of pumps. For equipment removal/installation in the basement, a floor access hatch was included. Lastly, piping and equipment design included valve operators at accessible locations wherever practical and ensured those out of reach could be accessed by a lift.

Summary

The redevelopment of downtown Lansing provided LBWL with an opportunity to improve the operation and maintenance performance of its chilled-water system. The project converted the primary-secondary system to a variable primary system and maintained the free-cooling system, reducing energy consumption and carbon footprint. Additionally, LBWL constructed an industrial facility without compromising the aesthetics of the downtown area.

References

- Nonnenmann, J. (2006, February). Chilled water plant pumping schemes. Paper presented at the International District Energy Association Campus Energy Conference, Albuquerque, N.M.

- McCauley, G., & Strause, R. (1996, September). Chilled water distribution pumping schemes. Paper presented at the Central Association of Physical Plant Administrators (CAPPA) Annual Meeting, San Antonio, Texas.

- Durkin, T. (2005). Evolving design of chiller plant. ASHRAE Journal, 47, 40-46.

A senior mechanical engineer and project principal for Stanley Consultants Inc., James J. Nonnenmann, PE, is responsible for business development, mechanical design, and evaluation related to central energy plants, power generation, and building mechanical systems. He holds a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. He can be contacted at [email protected]. A principal mechanical engineer and project manager for Lansing Board of Water & Light, Daniel J. Flynn, PE, is responsible for consulting, project management, and design related to the utilities' production and distribution facilities. He holds a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from Michigan Technological University. He can be contacted at [email protected].

SIDEBAR: LOW-DELTA-T SYNDROME

Causes of low-delta-T syndrome include:

- Improper coil or control-valve selection.

- Dirty coils.

- Mismatched design conditions.

- Three-way control valves, which allow bypass of chilled water around a coil at part-load conditions, result in lower return-water temperatures for all conditions except design. The mixing of the chilled-water supply and return water results in a lower-than-design delta-T, contributing to low delta-T syndrome.

- Supply/return mixing at building decoupler.

- Arbitrary lowering of supply-air-temperature set point.

- Coil piping configuration. Coils must be piped so water is counterflow to air. If coils are piped in reverse, the coil's heat-transfer efficiency will decrease, resulting in lower chilled-water return temperatures.