Our firm was recently involved in a new construction project in which several energy recovery ventilators (ERVs) were specified.

For those not familiar with them, an ERV is an air-to-air heat exchanger designed for enthalpic (that is, both sensible and latent) heat transfer between exhaust and supply air streams. ERVs – and the closely-related heat recovery ventilators (HRVs), which transfer only sensible heat – are not new technologies. The original run-around heat recovery coil was invented by Walter Glancy in 1973, and is still used today for applications in which the supply and exhaust air streams of an air handling system are not directly connected. Energy recovery wheels (heat and enthalpy) were introduced in the 1990s.

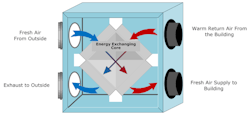

Their theory of operation is fairly simple. As the exhaust and supply airstreams pass through the energy recovery wheel, the rotation of the wheel facilitates the transfer of energy from the higher energy airstream to the lower energy airstream. In other words, the heat from the exhaust airstream is used to pre-heat the supply air during heating operation and, during cooling mode, the ERV cools (and with the use of desiccants) dehumidifies the incoming outside air by exhausting the rejected heat. The efficiency of the ERV increases as outside temperature and humidity conditions become more extreme, which is why these devices have made a comeback in the past few years.

On the project in which we were involved, the original ERVs were significantly oversized by the initial designer. And to make matters worse, the design called for 2100 CFM of outside air and only 450 CFM of exhaust, creating a positive pressure and effectively exfiltrating a substantial amount of conditioned air. The basis of design (BOD) was for variable refrigerant flow (VRF) systems, since most of the 9,600-sq-ft building has interior spaces similar to classrooms. However, the VRF systems selected – and budgeted – did not allow for more than 10-to-12 percent outside air, which was not sufficient to meet the requirements of ASHRAE 62.1-2013.

Although the original design concept was, apparently, to capture exfiltrated conditioned air, that was not reflected in the actual design. In the revised design, exhaust was provided from higher-occupancy spaces and routed to the correctly-sized ERVs, while maintaining some positive pressure. This was significantly less costly than trying to locate relatively small dedicated outside air units.

ERVs are once again gaining in popularity, but they – like other HVAC components – need to be properly designed and sized.

The author is a principal at Sustainable Performance Solutions LLC, a south Florida-based engineering firm focusing on energy and sustainability. He can be reached at [email protected].