A best practice for managing the installation and integration of complex systems is emerging. Known as technology contracting, it involves assigning a single point of responsibility to the management of the planning, design, installation, integration, commissioning, and service of low-voltage systems, business applications, and supporting infrastructure. Technology contracting can save time, reduce risk, and decrease construction and operating costs while ensuring that technology is deployed and integrated in an orderly manner to achieve desired outcomes.

Defining the Need

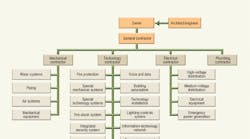

Traditionally, a building goes out for bid, and a general contractor wins the project. Separate subcontractors bid on the plumbing, wiring, lighting, HVAC, fire-alarm, security, communication, and specialty systems, and each subcontractor takes care of installing his or her own systems. This process can be sufficient when the systems being installed are simple and little integration is desired. However, it is not designed to serve the needs of larger, more technically complex projects.

Who is responsible for bringing a holistic approach to technology? Who can be counted on to bring forward the right solutions and install them in a way that ensures efficiency, coordination, and integration? Who remains committed after installation to provide ongoing technical support, training, and insight for future investments? With a traditional systems-management approach, one entity cannot fulfill all of those requirements.

Without a coordinated, enterprisewide approach to major technology initiatives, system and infrastructure duplications are common. Also, opportunities for integration and installation efficiencies are likely to be missed. It is difficult to take full advantage of these opportunities after a building is constructed. When deliberate expert attention is applied early in the planning phase, these pitfalls can be avoided. That is why building owners and their general contractors increasingly are assigning a single point of responsibility for technologies early in the construction process.

Revising the Contracting Model

Technology contracting augments the conventional building process in which subcontractors work under a general contractor. Technology contracting includes a manager who has an enterprisewide perspective on technology and the authority and technical expertise to make decisions and influence how the information-technology (IT) network--as well as comfort, communications, life-safety, asset-tracking, and business applications--will be chosen, installed, and operated.

With technology contracting, a building is created not as a collection of systems, but as a functional whole. Low-voltage technologies and other key systems are integrated to deliver the required results in full. Therefore, the time to consider technology is at the conceptual stage of a project.

While details can differ by project, this approach allows a technology contractor to manage planning, design, installation, integration, commissioning, and service of all of the low-voltage technology systems in a building. The benefits to technology contracting include:

- Time savings--effective project management means that all vendors work with clear direction and coordination.

- A reduction in risk and finger-pointing--a technology contractor acts as a single point of responsibility for planning, design, installation, integration, commissioning, and service.

- Lower capital costs--a technology contractor avoids unnecessary duplication of infrastructure and systems.

- Lower construction costs--better coordination means fewer duplications of effort and infrastructure, fewer change orders, and faster commissioning.

- Lower operating costs--a large percentage of a building's life-cycle costs accrue after construction. Intelligently deployed technology saves energy, reduces maintenance, and uses facility staff efficiently.

- An increase in system interoperability and opportunities for intelligent integration.

Why Now?

Technology contracting is not a new concept. Until recently, however, there has not been much demand to create a single point of responsibility for all of the technology used in the construction process. The industry is now ready to embrace the technology contractor's role in large, complex projects.

One reason for this change is the proliferation of technology. A technology contractor can help the building owner, architect, and general contractor plan the best systems, applications, and infrastructure for prospective tenants. The technology contractor is responsible for delivering, installing, and supporting solutions in every area.

Another key factor is the increasing convergence of building systems with IT and business systems, such as patient monitoring and nurse call in hospitals. Previously fragmented technology systems within buildings are converging on standard platforms, applications, and infrastructures. The demand for data exchange across multiple systems and disciplines is growing.

Systems now are able to communicate with each other, talk to other enterprise applications, and offer increasing mobility to users by delivering information anywhere at any time. More information can be obtained on a by-request basis and in a manner more easily understood by other systems and the people who want to analyze it. While possible, this does not happen without deliberate effort.

If integration is attempted after systems have been installed and construction is complete, the process is more costly, difficult, and time-consuming than if it had been planned all along. A technology contractor can consider the various technology systems and integrations up-front, coordinating the systems to live up to their full potential.

The Process

A technology-contracting relationship typically begins during the early stages of building design. The objective is to respect a project's budget while meeting the needs of the facility's prospective occupants. Involving a technology contractor early ensures that overall building architecture and systems are mutually supportive. The process results in mechanical and electrical systems that are efficient, optimized, and future-ready.

Planning. Effective planning is the first step in a successful technology-contracting engagement. Generally, a technology contractor brings together all of the stakeholders--the owner, representatives of various business units and departments, the consultant, the architect, and contractors--for a facilitated planning session. The planning session defines and prioritizes technological needs. It drives results that serve the desired business outcomes as cost-effectively as possible. Beyond facilitating the discussion, a technology contractor's role is to be familiar with the universe of feasible technologies, point out common packages and integrations, and recommend options to suit the project's budget.

Design. During the design process, a technology contractor advises the building-design consultant on the location of building-systems equipment, ductwork, and cabling. Elements are streamlined to maximize the efficiency, integration, and interoperability of technology systems. Early in the project, the technology contractor assesses the need for in-building cellular and wireless controls and other infrastructure. Involving a technology contractor in the design process ensures that every opportunity is seized to maximize systems' efficiency. Thoughtful design means fewer change orders during construction and system installation.

Installation and integration. Installers often operate within technology silos, such as HVAC, fire and security, IT networking, enterprise-system programming, etc. When systems are integrated, installers sometimes find themselves outside of their comfort zone. Opportunities for improper installation abound.

A technology contractor oversees the installation of low-voltage systems, including building systems, business applications, and supporting infrastructure. Installation subcontractors are chosen based on various factors, such as price and specialized expertise. A technology contractor ensures that installers coordinate with one another and designs are executed properly.

Commissioning. Commissioning is a systematic process of checking that all building systems perform according to their design intent and the owner's operational needs. Construction observation, functional performance testing, operator training, and record documentation are important aspects of the commissioning process. The commissioning process begins during the design phase of a project, from the documentation of design intent through to the construction, acceptance, and warranty periods. Performance verification allows a technology contractor to double-check systems before occupancy.

Service. Technology contractors commonly remain on board after a building is occupied to service installed systems. Because they are involved in planning, design, installation, integration, and commissioning, they have the "30,000-ft view" of how systems are supposed to function. Commissioning benchmarks performance, so a technology contractor easily can identify and repair systems that have ceased to operate at acceptable performance levels.

Every project differs. In general, the technology-contracting approach means turnkey design, installation, and commissioning of all low-voltage technology systems. A technology contractor helps a customer identify potential duplications and trim capital costs. Effective system design and monitoring can reduce expenditures on energy, maintenance, and upgrades.

The State of the Industry

Examples of technology contracting are becoming easier to find. The Shanghai World Financial Center in Shanghai, China, enlisted a technology contractor to lead the design, implementation, and commissioning of all of its low-voltage building and IT systems. Recently completed, the building is among the world's tallest. Installed systems include a building-management system, as well as wireless-distribution, closed-circuit-television, security, car-park-management, fire-alarm-protection, key-box, master-antenna/cable-television, central metering, water-leakage-detection, access-management, telephone-management, and public-address systems throughout the facility. The technology contractor designed all of the systems to tie into a common building-management platform for monitoring and control. Building controls, voice and data networks, and security will share a common wired and wireless infrastructure.

There also have been many excellent examples of technology contracting in the health-care-facilities market. Hospitals have all the usual building and IT systems: comfort controls, fire- and life-safety systems, and voice and data networks. They also may have nurse-call, public-address, paging, and other specialty systems. Nurse-call systems take full advantage of system integration. For example, they may be programmed to deploy human resources and equipment intelligently in response to certain coded alarms. A radio-frequency-locator service can locate people and equipment. When an alarm sounds, the service deploys nurses based on specialized skill sets, the priority of an individual nurse's outstanding calls, or physical proximity to the patient. Orderlies know where to find needed equipment. Silent vibrating alarms minimize noise and contribute to a more peaceful and patient-friendly hospital environment.

Technology contracting has applications in a variety of other sectors, including education, industrial, and life-sciences facilities. Nevertheless, it remains a new, if not totally unfamiliar, concept to many architects, engineers, and general contractors. However, many design professionals still believe that general contractors--in tandem with mechanical and electrical engineers--have sufficient expertise to coordinate and integrate systems. They usually do not.

To function effectively in a technology-contracting role, a firm must have knowledge about building controls, fire and security systems, IT networks and systems, and specialty business applications. The firm also must be well-versed in planning, design, construction, installation, and commissioning. Ideally, a technology contractor has the resources to provide maintenance and operational and management support after a building is occupied.

Integration among building, IT, and enterprise systems still is a young concept, having come of age only this decade. Few firms possess broad enough expertise to perform well in a technology-contracting role. In time, the discipline will achieve broader recognition, and specialized professionals and boutique firms may find niches within it.

Conclusion

The future of technology contracting looks bright. New developments in building construction have laid the groundwork for its growth and proliferation. In 2004, the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) issued its most significant revision of MasterFormat in 40 years. MasterFormat is the construction-industry's standard for organizing specifications for commercial and industrial building projects. In writing the revision, the CSI acknowledged that rapid technological advancements have made the old contracting model obsolete. Forty years ago, building systems fit into neat silos (such as climate and comfort, fire safety, and security), did not communicate with one another, and generally were regulated by operator-initiated, manual mechanical controls. The revised MasterFormat reflects the emergence of new controls and systems and the specialized expertise needed to design and build them.

Buildings are huge investments. Particularly in mission-critical environments, such as hospitals, life-sciences facilities, manufacturing plants, and large-scale commercial facilities, the efficiency and integration of systems can affect occupants' business performance substantially. Technology contracting means taking an enterprise approach to technology. It enhances integration, optimizes technology usage, and maximizes budgets. Technology contracting helps building technology fulfill its promise and building owners realize their visions.

Vice president of channel marketing and strategy for Johnson Controls' Systems business, James F. Dagley is responsible for the company's 14 North American distribution channels, including marketing, developing channel partners, alliances, and acquisitions. Formerly a captain in the U.S. Air Force, he holds a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and material science from Duke University and a master's degree in business administration from Chapman University.